It's the understatement of the millennium to assert that the trajectory of Mystic Searches development has not quite gone the way I'd planned it when I originally found those silly illustrations conjured up by my seven-year-old self. Back in 2014, when I happened upon the box of old illustrations, when I started dabbling into NES development and meeting the homebrew community, when I started asking questions about whether or not I could, I was certainly unprepared for the creative avalanche that was to follow.

For a decade now, this has consumed me. But I think what is most misunderstood about the journey is the external perception that it has been linear. That on a creative journey like this, there are a quantifiable number of benchmarks to reach some proverbial finish line. This is simply not the way of it. Not for a passion project such as this.

I could go down any of the many rabbit holes of how this has continued to grow and evolve. I could cite how four voice chiptunes plunked out on a MIDI keyboard became a dramatic, sprawling orchestral suite of rich, cinematic themes. I could cite how a derivative little paragraph of fiction written in 1987 has expanded into hundreds of pages of novelization and world building. I could demonstrate how the simple colored pencil illustrations that spilled out of a 2nd grader's hand have grown into towering visual lore.

But today, I want to talk about the hero of this world, Julian, and how such a long gestation cycle of this project has been necessary to turn him into the character that will become the avatar for many of you as you explore his world. I mean this both narratively and mechanically.

Let's look at how the character began.

The original concept for the hero was a nameless, caped knight, roaming a fantasy countryside with a magic sword (thank you, various colored highlighters), quiver of golden arrows, and mysterious crystal ball. His charge was to search the barren lands of some nameless, fallen continent (or, if it had a name, I do not recall it) to battle corrupted wizards, dragons, and monsters.

As a 7 year old, I had very few touchpoints for reference. This character was Atreyu. This character was Jack O' The Green. This character was Link. This character was a little Luke Skywalker and a little Galen the apprentice and maybe a little He-Man. Equal parts Conan the Barbarian and Perseus and pig herder Taran. This nameless hero was fully realized in my brain as this unfocused amalgam of all fantasy tropes I'd experienced in my mere seven years, with all the narrative or thematic depth of the sort of plastic action figure one might get at Toys R Us.

After sending the full box of concepts, level designs, faux manual, cassette tape with Casio keyboard soundtrack to the address in the back of Nintendo Power, and after that box was returned to me and retired to storage in the recess of my parents' backyard shed, and after I moved forward with life and personal experiences, the concept for the world of Mystic Searches and this nameless hero began to grow and evolve. Long before I'd rediscover these illustrations as an adult, the very rudimentary ingredients of Mystic Searches would continue to branch into new creative concepts, informed by growing life experiences.

A major brach of generational ideating on this idea happened when I was in high school. I found a love for strange fiction, science fiction, and cosmic horror. I began reading a lot of Stephen King and a lot of H.P. Lovecraft and a lot of Ray Bradbury and Piers Anthony. The nondescript, derivative continent of those childhood illustrations began to take shape as some external, tangential reality where the rules of physics and nature were malleable, and manifested in horrifying ways in our real world. The Martian Chronicles story The Third Expedition, King's Dark Tower series, At the Mountains of Madness, Michael Crichton's Sphere, various X-Files episodes, Rick Berman era Trek, and Piers Anthony's Incarnations of Immortality series all began to synthesize with my exploration of things like Dungeons & Dragons and the new battle deck game called Magic the Gathering and much more comprehensive video game RPGs such as Dragon Warrior IV and Final Fantasy VI.

On top of that, of course, I was dealing with real life traumas of puberty and unrequited love and all of the hormone-driven angst of being a teenager. I experienced the death of family members and friends. I experienced the joy of new passions such as creating music. I experience real heartache and real triumph, true friendship and bitter betrayal of ones so trusted. I became the real life villain in some peoples' stories while being the victim, or at rarer times the hero, in others.

With all of this life and growth and experience coupled with my heavy diet of fiction and fantasy, the stories I wanted to tell grew and morphed. The reason for their telling changed. But no matter what direction they pulled or how the matured, they were still inextricably tied to those illustrations for Mystic Searches.

The ambiguous hero, once designed as a poor emulation of greater works, soon became my avatar. He became less a bannerless knight in a traditional sword and sorcery story, and more an extraordinary vagabond searching exotic realms for meaning and purpose. His battle was less against literal dragons and wizards, and more against existential threats.

In the early 2000s, putting me at my early twenties, I was touring with a rock band. Out of this came a second iteration (and a complete top-down rewrite) of Mystic Searches mythos in a nameless novel, where a young boy named Jeffrey with acute and often dangerous empathic abilities, was kept captive in am academy under the guise of exploring his gifts, but with the reality of tempering his potential threat to a greater status quo. After meeting a suicidal Sara, he begins to question whether his own depression had been contagious or whether he had been empathically enveloped by her bleak perspective. He leaves the academy with a band of vagabonds and ventures "beyond the veil", into an allegorical world where he learns to transduce these empathically charged emotions into a sort of psychic energy, which allows him to combat the influence of those imposing the status quo, if only to regain full control of his individuality and emotional capacity.

The entire story was a somewhat pretentious metaphor for the independent spirit of musicians in the landscape of the impenetrable music industry. That frustration of the empathetic language of music being industrially whipped and beaten into commodity and sold as easily digestible product was my great war at the time, so of course it made it into my prose.

But the lone hero setting out into a fantastic, barren dystopia was a very colorful and topical veneer over the existing bones of Mystic Searches. Yes, dragons were phantoms, corrupt wizards were political opportunists, the simple biomes with random names took on more complex, interwoven context, and our hero was more likely to wear ripped corduroy than shining armor, but the meat of the thing was the same, as if my seven year old self had looked into my future through a crystal ball to try to mine inspiration for a story without yet possessing a suitable point of reference to chronicle what he saw there.

Inching closer to the rediscovery of the box containing the 1987 Mystic Searches art, I set out to revisit the entire concept of The Veil explored in the previous iteration, and wrote a novel called Beyond The Veil (ironically, Austin McKinley, who would go on to become my production partner on The New 8-bit Heroes and ultimately Mystic Searches, was one of the first test readers of this novel). Beyond the Veil starts out more like a fairy tale, following young Benjamin, a young child who lives with his parents in an isolated forest. He has an obsession with what exists out beyond the gnarled trees, but is constantly told there is nothing more of the world to see. One day, he inadvertently invites the something more into his safe little world only to be thrust into a world beyond the veil, a place which is malleable to his perceptions and fears. Joined by a sentient firefly, Eura, a very capable monster called Spinder who feeds off of his fear, and a girl-shaped abscess in the fabric of his reality that he names Lily, he sets out to find the mysterious Gadbeau who is willing to give young Benjamin a permanent and indestructible facsimile of the world he remembers in exchange for corporeal form.

This story was also very allegorical. It was about the frustration of the creative process. It was about the concrete reality of these places and characters (or melodies or brush strokes) in the mind of a creator, despite their abstract nature. It was about the compromises that come with realizing these ideas, and the innocence that must be shed to manifest them. I was actually very proud of the first half of this novel and all of its ambient weirdness. One can actually read an excerpt here. But it took a year to write the second half and I've never liked it. I had bounced out of the groove, focusing on getting married and adjusting to life in Florida at the time. I was of the mind that I would return to it for a redraft to really do the first half justice.

And then, I found the box.

When Austin and I began creating this game, without any intention of building anything that would take more than a week or two, we futzed around with a pretty direct adaptation of these illustrations, updated through his capable artistic hand of course. The nameless knight who planted the seed for this whole story was back, fighting monsters and dragons in a nondescript wasteland with his trusty crystal ball.

When the concept began to make Mystic Searches into an actual NES game, the concept never even occurred to me that Beyond The Veil was really a distant relative with so many obvious ties to those old illustrations. That discovery came as we battled one significant question: how much did we need to preserve in order to pay off on the original ideas, and how much could we allow our modern sensibilities as artists and writers and storytellers encroach without damaging the intent of the thing?

This fork in the adventure began like this. A title screen that has a lackluster logo with the words Mystic Searches, and a nameless 16x16px hero running around a zelda-esque four screen map. This was proof positive that we could make a NES game, though at this time we had no concept of exactly what we'd be able to create.

It was around then that we talked about concept, and the balancing act I mentioned above. Should this hero be the nameless knight, crisscrossing a nondescript world of derivative biomes to kill monsters and slay dragons because...something about good and evil? What exactly did the story of Mystic Searches mean to me all these years later?

One thing that became evident - and I remember thinking about this while on my early morning sunrise runs as I was trying to get in shape for my wedding, very early in the process of making this game - perhaps Mystic Searches should be about a hero who failed because of his youth and inexperience, returning as an adult to the world he had been powerless to save. Maybe Mystic Searches was a self-referential autobiography.

While that was summarily dismissed, the prospect of our hero being young and inexperienced as I'd been when I'd first conceived him ended up sticking. The irony, the young and inept me had dreamt of a capable adult knight, while the adult, capable me imagined the hero as an innocent kid with his life still in front of him.

Early on, there was also the decision to veer in some ways away from hard fantasy. Maybe there were dragons, but not necessarily castles. Maybe there were royal soldiers, but not necessarily a monarchy. Maybe there were wizards, but not in the traditional sense. And most certainly, give our hero something other than a sword with which to save the day.

The crystal ball, though? Looking through all the original 1987 concept art, it was so fundamental that it had to stay. And the idea of a lone wanderer was just...right. So as we started plotting the NES game, Julian became a vagabond musician, who had some sort of relation to a romani-like tribe of spiritualists with a penchant for crystal balls.

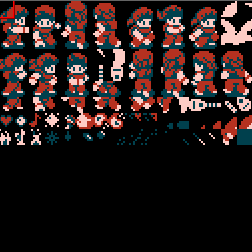

There are admittedly some early concepts by Austin for a character that would fit this description that have been lost to time. They were very cartoony, leaning heavily into NES constraints. Then, Austin arrived at this for the new approach to the character that we named Julian (you'll also see our first abysmal attempts at creating sprites for this character).

Pushing and pulling on this design really helped us work out the basics of the character, which became a center point for designing the character's world.

As art is not my forte, and Austin was unaccustomed to the soul-shattering limits of the NES, friend of the project Jherin Miller leant his skills to create the first directly usable art - it started with some stylized illustrations and then gradually became sprite art.

When dealing with the NES (and this will come back later), it's not enough to deal with color limitations. You're also fighting the amount of graphic data that can be loaded in at a time. This gets more challenging with larger graphics. So, for instance, a 16x16 pixel character could, conceivably, have much more fluid animations or more varied behaviors than a 24x16 character, because you would need an extra two tiles for every single frame of every animation for every action in the latter. However, a 24x16 character gives more room to be unique with extended detail at the expense of more complex animations.

Ultimately, we settled on a 24x16 character with limited (and some re-used) actions. For instance, his idle stance did not animate, and served as the crossing animation for the walk cycle. We tried both with a nose and without a nose. And we tried to imply diagonal movement.

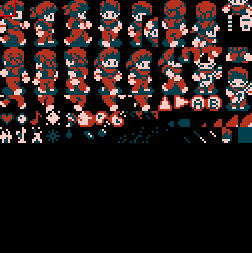

Starting to think about antagonists and NPCs, working through iterations of different sizes, and even thinking forward to the kickstarter, this was the first major graphics dump that I used to start making Mystic Searches into a NES game.

At this point, neither the narrative nor the mechanics were really considered. In terms of graphics, we had a somewhat generic but functional character that could move in four directions and attack with a weaponized lute. We also could reuse the attack animation to use a projectile attack with his crystal ball. We had to set about cranking on getting code to support these mechanics and animations. And I recalled one certain detail that my 1987 year old self wanted in this game. I have the distinct memory of wanting a top down adventure like Zelda 1, but with the platforming and jumping mechanics of Zelda 2. Now, to a 7 year old, what exactly that entails is nebulous. It's like talking about 4 dimension space to a non physicist. It's easy enough to say there are more than three dimensions, but it is a wholly other thing to ask a person to draw a 4 dimensional shape. So it was with creating a z-coordinate in a top down game.

But after working on this project for about six months, learning the ins-and-outs of assembly, working through concepts, and getting some simple animations (keep in mind, all of this was from scratch - there existed no engine for any of it yet) we had enough to show as a very simple proof of concept.

One of the things that made it all so frustrating was trying to fit graphics that could represent the mechanics inside the space in video memory we had reserved for the player (and other game objects, such as weapons or effects). There is an area 128 pixels tall by 128 pixels wide (denoted by 16 rows and 16 columns of 8px by 8px tiles) that can be used for backgrounds, and the same for sprites, which make up things like the objects in your game. At this point in development, we had no idea how we'd be changing out different sets of graphics for different screens. We didn't know how many different types of monsters we would have on one screen. We didn't know how many different types of items we might need on a screen at a time. The first completely arbitrary layout in memory for graphics (and some of the early monster treatments) looked something like this.

All this is to demonstrate that along with figuring out how to narratively construct this character, and how to graphically construct this character with the limited colors, it also had to exist within the bounds of what the tech could handle from a programatic standpoint. It became a volleying match of importance. More player animations meant less monsters, or less effects. Maybe we could get away with simpler spells graphics, but it would look less exciting. Maybe we could get away with one shadow sprite, but then it would be harder to gauge the actual height off the ground. Maybe we could use background tiles for HUD elements, but then we'd have to sacrifice a color palette for them. Maybe we could look at our player animation tileset and make hard decisions on reusing certain tiles that looked similar enough, but it would make the animations look just a bit off (good examples are reusing the same legs for standing forward as standing backwards, or reusing the idle frame for the walking's passing frame).

This sort of push and pull came to define the player, and how the pieces of the player could fit inside the puzzle determined what the player was capable of. We'd conceived of a slash animation rather than a stab, but it required too many tiles considering that would be a 3 frame animation including diagonals. We'd conceived of a more elaborate ground stomp action, in all 8 directions, but that required too many tiles. Every time we made an optimization choice to make sure we could fit what we needed in the finite space, it came with big consequences for the player behaviors or mechanics, ultimately affecting how the player interacted with the background or other objects. All of that informed necessary alterations to level design, puzzles, and monster interactions. Those changes informed necessary alternations to narrative and the uniqueness of the player.

Esepcially at that time, with no tools and no real skeleton, building the tracks as the train was coming as they say, making a NES game and its central character became much more like a slow spiral inward towards the target rather than a linear path to creation. People have always asked me "How long will this game take to create?" The reason that it's impossible to answer is that. It's not linear. It's not a thing that can be calculated.

Then the movie was released. My first son was born. People got their first look at Julian in Mystic Searches.

Many mornings were spent cranking on working out the bugs while my newborn son watched me chug copious amounts of coffee from my novelty mug (my wife bought me that ridiculous thing, blame her!).

There came a point in time where I found myself backed into a corner in terms of code. A little explanation without getting too technical. The NES hardware has the ability to see 32kb of data at one time. That's it. That's all. Ever. However, games can obviously be bigger than 32kb. The way games get around this is they are able to basically swap out sections of data as the game goes along. So a really easy to understand example - I could load data for levels 0-9 on one memory bank, and then 10-19 in another memory bank. If I am loading data for any of the first ten levels, I need to swap in bank 1. If it's dat from the second set of ten levels, I need to swap in bank 2.

Our game uses a particular memory mapper to handle this. And this particular mapper keeps a static 16kb loaded at all times, and allows you to swap out the other 16kb. The problem is that some things need to happen in the static, and not the variable, bank. That's a whole other conversation best reserved for another long post, but for now, just know that I was running dangerously out of room in the static bank. This meant that any time a bug or issue was found, it was nearly impossible to tech, as I couldn't even write debugging code without running out of room in the ROM!

While there was still room in the 512kb or ROM for data (things like more music, more graphics, more levels, more dialog, etc), our space for actual programming was used up, making a lot of that extra space moot. We did some optimization, we did some code-cleaning. But really, we knew that we had a finite sort of box that was almost out of space for our Mystic Searches game.

This is actually a look at an image of our game as seen through Shiru's awesome memory management tool, the NES Space Checker, which denotes available space in each bank of a NES rom. These are the last three banks. The last bank you see labeled $1F is the static bank. You can see, it is completely full. In fact, if I'm not mistaken, there were a mere four free bytes of data. That's all. The only way to free up space would be to tear down all of the functional mechanics, optimize each in turn, figure out better ways to manage the memory now that I knew so much more, and effectively build it back from nothing.

I remember having the conversation with Austin - imagine if we'd had the tools and knowledge that we had now when we had started this project, how much better we could've planned our memory and how much grander we could make the game. And I remember his response was...well, why couldn't we just sort of rebuild it?

At first I balked at this because I wanted to get the game that people had seen in the film into people's hands. I knew they were waiting for it. Then, I came up with what I thought was an ingenious idea. What if we made the current iteration of things a prequel game while we rebuilt? It would still be a full, playable game that could satisfy those who were impatiently waiting, but for this passion project called Mystic Searches, we could take as much time as we needed to build it back bigger and better. Thus, Mystic Origins was born. We altered the story and world slightly, and put Julian in a position to first meet the mentor in a quasi trial to gauge his worth and aptitude.

In doing this, and getting all the functional mechanics in that we had intended for the completed game, it forced us to do two important things. First, it forced us to refine the in-house development tools that we'd created (at the time, called the Mystic Searches Screen Tool and Game Engine). That first item allowed us to much more easily play with the layout of our graphics as they would be loaded into the game. It also gave us more options for accessing and attaching scripts. Here is what that looked like, with a glimpse at the graphics layout. If you look carefully at the graphics layout, you can see some of the compromises made when you compare this to what was posted earlier regarding space for the player, space for the effects, and how these things were utilized. One notable difference is in the bottom rows of the sprite page. The magic was reduced from a two-tile projectile with a tail, magic was reduced to a single tile in order to fit more necessary content for collectables, effects, and and HUD elements (such as which relic is armed).

But with our updated tools, we were able to crank down the hard edges of the game at that point, and officially put out Mystic Origins.

Julian embarked on his first adventure. From meeting with his would-be mentor Mystic Paen in the old, forgotten temple, through the Mossyglen Maze, through the poisonous swamps of Brakwater Bottom, into the town of Dariav to search for an old wizard, to the depths of the Palacido Forest and finally to the Hamishago Mines where something terrible and unnatural terrorized the miners.

The game featured a day night cycle, a shop an inventory system, basic quests and rewards, and mulitple biomes including the grassland, the swamps, a cave system, an urban district, farmland, a forest, and the mines. The narrative of the NPCs was rewritten to reflect a different time and place than Mystic Searches intended setting, so that we could make this prequel quest contain whatever narrative devices we wanted without contradicting existing concepts planned for Mystic Searches.

Releasing this game into the world gave me a lot of important feedback. What was fun, what was unintuitive, what worked and what didn't? What read well, what was murky? What did people miss when they first played, and how could it be made clearer? In short - what did people like, and what did people dislike?

Mystic Searches very literally started the process of being completely reconstructed, alongside the base engine for the Mystic Searches Screen Tool and Game Engine, which very soon thereafter became NESmaker.

But the story of NESmaker is the story for another time. This particular story is about the development of the hero, Julian, and how time and the development cycle changed and evolved this character.

In terms of mechanics, we really wanted to start doing a lot more with z-depth. Even as early as Mystic Origins, Julian had the ability to Jump, and that allowed us to set up a few platforming areas and give a stomp ability. However, there weren't a whole lot of opportunities to feel like he was climbing stairs or mountains, and that seemed a shame. I worked incredibly hard on developing a system for z-depth which would create an illusion of depth rather than spending a byte-per-tile to give ACTUAL depth (which was actually considered at one time, but it would have HALVED the number of screens possible with all that extra bloated data!).

I did, however, come up with a solution - new collision types that denoted if a tile was a jump up type tile / fall type tile, and that allowed me to create these limited stair type mechanics without changing much of the physics engine. It really opened the world to feel like it had depth!

Another inevitable consequences of making NESmaker was that it expanded to those excited for Mystic Searches, and even to those who had skills in developing retro game assets that wanted to be involved. One user, Franco Ledda, looked at Mystic Origins and created a whole new suite of assets without even telling me, then shared them with me letting me know I could use them if I wanted, expressing he just wanted to help the game be cooler. Julian went through quite a significant facelift.

Not only was the sprite much more refined with additional character, it also did something that Mystic Origins iteration did not - actually had animations for diagonal motion! Mystic Origins allows for diagonal movement, but the sprite faced forward or backward (comparable to Link to the Past). I was content with that considering the system's limitations...that is until I saw this in context. Then I needed to figure out a way to work this fully realized 8 directional animation in.

That also meant, however, diagonal attack frames.

What resulted was another round of Tetris with the graphics page. Now we had more tiles that would need to be worked into the same space, and we had to re-think the entire engine of space reserved for the player and game objects versus the space reserved for monsters and NPCs.

Here, you can see the area with the red rectangle as the new space for the player and game objects, with the area with the blue rectangle as the new space for the monsters and NPCs. A lot of concessions had to be made, reusing like-looking, "close enough" tiles where possible, mirroring actions that didn't make sense to mirror (he uses his left hand this way, but his right had that way, etc). But this certainly made for a more compelling, more dynamic version of the character for this new version of the game, and this layout became the default, fundamental split of the graphics page for NESmaker as well.

Another major advancement of the project was in terms of its narrative. When I originally set out to create this thing, I had no compass. I had no functional understanding of how much various pieces of data would cost in terms of memory, or how much of what could fit where. I only had a loose concept of how to string it all together. And at that time, everything was being created by hand. Text strings were literally being written out character at a time in big tables. Screens were being written out in a series of tables (tile table, collision table, and attribute table which handles things like color). But now, with the aid of our in house tool, I could much more readily assess how changes affected the ROM size, and much more easily reorganize data without breaking everything.

This led to a grander understanding of how much lore I could squeeze in, how I could work in more graphics for more biomes, how I could work on unique mechanics for boss monsters or special screens. As a result, it became much less a novelty project to see if I could, paying off on a 7 year old's wild ambition, and much more a creative outlet for me as an adult.

This really brought out the writer in me, and I began cranking out the narrative. Julian's world began to grow full of colorful characters and rich lore. Gone were the bland villagers and derivative plot elements. This character began to represent something more, and his rigid world and all of the players in it began to take on a beautiful complexity.

This led to novelization and comic treatments (thanks to Austin's skill as a graphic novel illustrator), which explored a more extended understanding of the character than can necessarily fit inside of an 8-bit game, but was important to understand in order to hit the right touchstones in the game.

Julian's counterpart, Majorie, became an incredibly important, and very fleshed our character. The meaning behind all that transpired during Mystic Origins grew. And as we did more to flesh it out and see it fully realized as a dynamic world, it all started to feel...a bit familiar.

Tracing backwards through evolution of the original Mystic Searches ideas, first formed by a 7 year old me in 1987...

If I thought back to my first untitled novel that I'd written when I was touring, it was about:

A young vagabond Jeffrey, being held captive under the guise of fostering his unique empathic abilities.

He meets the lavender dress wearing, fiery haired Sara, who has a strange relationship with a monster.

They set out together on a quest that challenged what they understand about the world.

Then, how that evolved into Beyond The Veil, about...

A young Benjamin, in an isolated pocket universe to keep him and his unique potential empathic ability safe

He meets the glimmering abscess he names Lily, who has a strange connection to a monster.

They set out together on a quest to challenge what they understand about the world.

And now, how it was manifesting in Mystic Searches...full circle, the NES game I'd imagined as a child, that had been pushed through 30 years of evolution, leading through those two major touchstones of my creative life, arriving ultimately to...

A young vagabon, Julian, being held captive under the guise of fostering his unique, magical musical abilities

He meets a lavender dress wearing, fiery hared Majorie, who has a strange relationship with a monster

They set out together on a quest to challenge what they understand about the world.

This all suddenly reminded me of the James Baldwin quote.

“Every writer has only one story to tell, and he has to find a way of telling it until the meaning becomes clearer and clearer, until the story becomes at once more narrow and larger, more and more precise, more and more reverberating.”

I had been developing the Mystic Searches NES game and its surrounding lore for half a decade by this point and had not realized that this applied to me as well. Those three parallel points are just the high level illustrations of archetypes and very broad themes, but it was down to the details, too. And through this lens, I began to look at this silly NES game I was making in a whole new light.

And with this light, I was able to fill in a lot of blanks about who this character was, where he came from, what his thematic purpose was, beyond the two or three sentences you might find in a traditional NES manual. Looking back, I feel like to that point, I was still writing forward, building the character around what could be conveyed. It was at this moment that I truly started appreciating his place in the world and why this story was personal to me.

And with all that articulated came a couple of great new illustrations from animator Sunder Raj.

And then came the dark times. We all remember them. It was a period of chaos and unrest, that included (but was not limited to):

Covid, and the inability to send my child to daycare

My parents shuttered with us in our home during lockdowns

The birth of my daughter

The decision to leave Florida and move 1500 miles

The start over in a new city

The start of a new career

While everyone experienced these things and all the complications that resulted from them, the cumulative effect of them really took a toll on forward progress for Mystic Searches for a bit. Focus went into the world; working with a multitude of artists to help better flesh out the world based on the growing game bible.

Biome Concept Art by Autumn Rose

Bestiary Concept Art by Autumn Rose

The game mechanics were updated to support this broad range of new monsters, tilesets were designed for these biomes, and bosses that guarded these biomes were logically conceptualized.

Here are a few of the boss concepts alongside their sprite counterparts, the latter created by Fernando Fernandez.

Narratively, things had evolved in an amazing new direction. However, the pandemic had a few unexpected consequences on the technical part of the project. At the time, I'd been working with Infinite NES Lives on production of the boards. However, the 512kb boards were becoming more and more difficult to source. However, INL had a solution. They had a somewhat reliable pipeline to get 1mb boards (twice the size) despite shipping and parts difficulties. It wouldn't affect the price much, and it would just mean that the game would have an awful lot of wasted ROM space.

To which I replied "I'm not going to NOT use that extra ROM space if it is available". So INL worked with me to produce a "Mystic Searches" variant of the memory mapper that could make use of 1mb (that would be...64 memory banks of 16kb in size rather than 32 banks). Now, don't forget, the NES still is only capable of seeing 32kb at a time no matter how much memory you stuff into that plastic shell, and mapper 30 still meant one static 16kb bank with one 16kb swappable bank, so the above memory would still exist and we still had to be very frugal with mechanics so that it didn't eat that precious static bank space all up.

But, this did provide a strangely unique opportunity to work in some more of this lore that we'd been building. It ended up manifesting as mini games that tethered into the main game; they helped provide narrative cues as well as unique mechanics to acquire new weapons or items or unlock secrets.

I had elbow room to create completely unique substates for things like map with unlockable areas, a quest system, complex shops with barter systems, a material management system for crafting weapons and items. It also allowed the creation of larger graphics in cut scenes and game sub-states to really help give identity to the various races and important characters in the game. In some ways, all of this helped give the player agency over how they could play. For instance, a player could scour the open parts of the continent to find materials to create a potion that would allow for immunity against a certain area debuff, or they could complete a specific quest for an NPC that would give an item that would null that area debuff. They could upgrade their weapon behavior for more diverse playing options, or keep it simple and straightforward. It could also lead to multiple endings with achievements. A player could get all of the weapon upgrades for an achievement, all of the map unlocked for another, complete all the quests, fill the bestiary, etc.

With music being so important to me, and being so important to the character, I worked with another composer to arrange the entire suite of chiptunes as a fully orchestrated soundtrack; an amalgam of the songs in a way that gives the vibe of the entire story of Mystic Searches through a musical arrangement.

I also continued the novelization, exploring both Mystic Origins and Majorie through the lens of Mystic Searches lore.

A spooky tall, told my Julian, which gives a narrative look at the monster from Mystic Origins

A little background about Majorie, a very important side character

Mystic Searches, the game, moved into testing phase. And man, did a lot of things start to break!

Without getting too technical, I'll say that the NES has a finite amount of RAM. If you're not up to speed with computer lingo, RAM, or Random Access Memory, can be thought of as memory that holds variable data (whereas ROM holds static data). So, for instance, song data is ROM, but the play counter for where a song is during playback is RAM because it's always changing. Many things rely on RAM in a game. Think of everything that changes of the course of a game - the player's position on the screen, what level he is on, what monsters exists, how much health the monsters have, what weapon is being held, a power meter, the status of a quest, what is in the inventory, what frame of animation every object is on, and how much time until the next frame pops up, the current game state, and so on and so forth. Because RAM is so finite, often times the same RAM variables are used across game states. The idea is, if they never conflict this won't be a problem. For instance, there are no monsters on a start screen, so conceivably I could use any RAM space reserved for monsters on a start screen for other start-screen-needs without impacting what happens when I'm on a screen that does have monsters. That's a fairly easy example to understand.

Now, Mystic Searches code is written in a way that there should never be an instance where there is corruption of these variables. That is to say, it should always be when jumping to a different game state, using the variable space in a new way, then jumping back to the former game state. Everything should work as expected.

But of course, Murphy's Law sneaks into all things. And as Mystic Searches was being tested, we continued to find game breaking bugs that seemingly had to do with these memory leaks.

At this point, Mystic Searches was massive. Imagine the biggest tangled ball of wires you can imagine. And going in to make changes in some spots for testing had to be surgical, because tweaking the code in one place could cascade and affect everything else. Not only that, while the code was much more optimized than it had been back in the Mystic Origins days, the sheer volume of more meant that we were once again finding ourselves with backs against the wall with memory left in the static bank.

That means, in short, in order to even begin testing a particular part of the game, we'd have to remove whole parts of the game or entire mechanics to test what seemed to be broken, then apply a fix, then put the removed part back in, most times to find that the added fix made the code overflow, meaning time had to spent to optimize where possible and make tough decisions on cutting or developing brand new methods from scratch to do similar things with less code. It was this, over and over.

And many times, we'd find false positives. We'd patch as described above, find that things looked good. And then after playing the game for 5 hours, find the problem suddenly appear again. Or worse, plugging the code would look like those cartoons where a character plugs a hole in the boat and another springs a leak.

Massive overhauls had to, again, be made to the way graphics were loaded to the screen, the physics engine, the collision system, many of those special screens. It got so frustrating that I developed a cheat screen. This cheat screen (which is still in the ROM this minute!) allows me to put the game in ANY state. I can give myself any buff, start on any screen (or special game state), set what's in my inventory, what time of day it is, what weather conditions, what's in my bestiary, what quests are completed, etc. This cheat screen alone took over a month to integrate, just so we'd have a quick in-game system to be able to attempt to reproduce issues at any point.

This has generally proven worth it. Many of the underlying bugs have been found and eradicated. While I still expect there to be issues and little quirks (even the best top tier NES games had their weird exploitable bugs, right?!) the goal has to be to get rid of all the game-breakers.

While all of this was happening, Julian went through one more major game update. There were a bunch of rough edges for the character's animation that we had to just accept because of the limitations of the system. I am packing a lot in to this very finite space. Let's talk about what Julian can do as a character.

He can stand and move in 8 directions.

He can stab in 8 directions.

He can cast spells in 8 directions.

He can upgrade to a slash attack in 8 directions.

He can jump.

He can do a spin-ground pound attack.

He can do an in-air spin attack with his weapon.

He can do a dash move in 8 directions.

He can do a super ground pound shake with his weapon

He can play his lute

He can hold up prizes

Oh, and let's not forget that since he can jump, that means any in-air actions need to include a shadow. But since there is a scanline limit, we don't always want to draw an extra shadow attached to his feet - we want to draw his on-the-ground animations with the shadow as part of them, and only draw a separate shadow when he's actually in the air.

Working with Fernando Fernandez (sprite artists extraordinare!), we revisited all of these. I was never happy with the slash (because it was simply doing the stab in three directions rather than something that looked like a stab). I'd had to really cheat on the super ground pound. The dash had no defining look, he just moved with his sword out. Basically, the compromises were really weighing on me. Jettisoning what we knew about the graphics and animations for the character, the space they could fit in, and just thinking about it as if we were making this without the constraints of the system, we built gif.

And then, we broke it down into every frame needed to actually make this happen.

This sheet does not contain things like game objects and items, the player's shadow, etc. And remember, this is the entire size available for game sprite graphics in a given game (the red and the blue...though dipping into the blue means less graphics available for monsters):

So parallel to continue to test and work through bugs, rebuild systems, I was also working through these graphics to see just how close I could get to representing the full spread of animation and mechanics in full 8 directions.

And then I considered a trick. It's a compromise, yes, but...could it be a middle-ground solution?

See, a tileset has four potential frames of animation. Technically you can load four tilesets at a time, and cycle through them to create background animations. Unfortunately, it's all or nothing - you can't animate the background this way and NOT the sprites. It's changing out the whole tileset for the next, So generally speaking, your OBJECTS (your player, power ups, etc), would stay the same over all four tilesets, while your background would have subtle difference (grass swaying, water running, windmill turning...whatever) on each of those tilesets. You can then animate the background at any speed, and it would seem to operate independently of anything going on with the player, since whatever frame you are on, the player's graphics would be exactly the same.

But what if I could make the compromise to only have 2 frames of background animation. That's still enough to make grass dance and windmill be upright then diagonal and trees to flutter and water to bubble. I would put tileset 1 to be frame 1, and tileset 2 to be frame 2...but I'd also put tileset 3 to be frame 1 and tileset 4 to be frame 2 for the background. But then I could change the player graphics on one and two to get half of my player animations, and 3 and 4 to get the second half of my player animations.

Confusing? Let's look at an example:

(frame) | (what is on tilest) | (what is on sprites) |

FRAME 1 | Grass UP | Player Passive Actions |

FRAME 2 | Grass DOWN | Player Pasives Actions |

FRAME 3 | Grass UP | Player Attack Actions |

FRAME 4 | Grass DOWN | Player Attack Actions |

So if I am just standing still or moving around, it will show frames 1 and 2. I can show the animations for walking and running, and the grass is oscillating between its two frames of animation.

Now, I attack. It adds two to the actual frame that I am on. If I'm on frame 1, it shows me frame 3. If I'm on frame 2, it shows me frame 4. The grass is still oscillating at the same speed between the two frames of animation. However, now I have the attack animations shown, so I can run the player's attack animation. When the attack is over, it stops adding 2 to the frame offset, and i'm back to showing frames 1 and 2. The grass never stopped oscillating at the exact same speed, however, I was able to double the amount of player tiles I could utilize with this technique! More player tiles equals more animations. Here is the result of Julian, able to perform all of his main actions in game, against a black sandbox screen.

And here are the tiles in the sprite area of the tilesets in those two different configurations, one for passive movement (left), and one for attack (right). You can see things like effects, game objects, shadows, and a full tile mask sprite exist in both:

Fortunately, this update was mostly a cosmetic one (aside from having to update a handful of the monster animations to fit). But now, the movement in all 8 directions is much more gratifying!

Creating this game has not been a linear path, and it continues to be a spiral towards a target. One thing is for certain, though, this project has been about the journey and not the destination. Seeing this character grow and his world develop into something that is a weird compression of my creative work since I started making things all the way into my adulthood all in one project has been incredibly fulfilling, and had I been just interested in cranking out a commodified novelty product, it wouldn't be nearly as interesting an experience.

Comments